This year I taught my undergraduate course Anthropology for Liberation at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington after a two year break. As readers of this blog will know, I regularly post about the readings I assign and the assessments I design for this course. Like previous iterations, this year I modified the course in response to the current academic and political climate, student feedback, and ongoing scholarly conversations about what it means to practice an anthropology “designed to promote equality- and justice-inducing social transformation,” as Professor Faye V Harrison (1991, 2) – whose edited book this course is named after – describes it.

This is the first in a three-part series reflecting on changes I made in 2025. This post discusses what happened when I dropped a book from the reading list. Future posts will explore how I redesigned assessments (including AI reflections and game design options) and what I learned from introducing role-playing games in class. Some of these changes worked well, while others taught me an important lesson about the gap between pedagogical intentions and outcomes.

Changing the course readings

What does it mean to teach a course titled “Anthropology for Liberation” while watching genocide unfold in real time on our phones, navigating AI-generated misinformation, and grappling with what feels like an accelerating unraveling of democratic norms? This question troubled me as I prepared the course. I decided to address it at the outset by adding new readings to Week 1. However, this created a practical problem: I had developed the course to use a close reading approach I outlined in a previous blog post, which involved assigning four books to read throughout the trimester and working through them in class. Adding new readings at the start would push the books back in the schedule, and previous feedback from students indicated that working through a book in the final weeks of the trimester was unsatisfying because they were so focused on assignments that they weren’t able to meaningfully engage with it. So, I decided to drop one of the books from this year’s reading list.

What I added to Week 1:

- Tolentino, Jia. 2025. My Brain Finally Broke. The New Yorker.

- Harrison, Faye V. 2025. “Afterword: Toward an Anthropology of Liberation.” In The Anthropology of White Supremacy, edited by Aisha M Beliso-De Jesús, Jemina Pierre, and Junaid Rana, 361–72. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

In our first seminar, I addressed the challenges of teaching a course like this in the current moment by doing a close reading of these new readings. I selected a series of quotes from each piece and read them aloud in class, pausing to discuss the work that a particular word or sentence was doing and to connect it to our course. I started with Jia Tolentino’s comments about phones as “time-eaters”:

The phone eats time; it makes us live the way people do inside a casino, dropping a blackout curtain over the windows to block out the world, except the blackout curtain is a screen, showing too much of the world, too quickly. As Richard Seymour writes in the book “The Twittering Machine,” this avoidance of time’s actual flow, this compulsion toward the chronophage, the time-eater, is a horror story that is likely to happen only “in a society that is busily producing horrors.” (Tolentino 2025)

This prompted students to discuss how they use their phones and the disorienting experience of scrolling through images of hospitals being bombed and screaming children in Gaza alongside influencer content. Several students spoke about the desensitisation to suffering that can occur when such images go viral, while also acknowledging the privilege of being able to scroll past at all. They also made connections with Palestinian solidarity events here in Aotearoa and the November 2024 Hīkoi mō te Tiriti.

The discussion we had led nicely into the quotes I selected from Faye Harrison’s chapter, including her observation that “White supremacy, accumulation by dispossession and expropriation, and the ecological crises of environmental injustice and climate change are global problems that cannot be dealt with simply within nation-states. We have to build multilevel and multilateral bridges that will permit activists to combine forces in greater measures of unity despite the differences and distances between us” (2025, 369). Harrison also argues that “As individual scholar-activists but especially as participants in wider collectivities and coordinated webs of connection, anthropologists have the capacities to align themselves with, become accomplices with, and advocate on behalf of sociopolitical processes aiming to effect meaningful, substantive change” (2025, 370). Working through these quotes helped set up the guiding framework for the trimester.

What I removed from the reading list (and how it affected the course):

The book I chose not to read this year was Ashanté Reese’s 2019 Black Food Geographies: Race, Self-Reliance, and Food Access in Washington, D.C. In previous years, this book worked well alongside the collaboratively authored Imagining Decolonisation (which provides an excellent introduction to ideas of decolonisation as they play out in Aotearoa); Ranginui Walker’s Ka Whawhai Tonu Matou: Struggle Without End (often described as one of the best histories of Aotearoa and which I think makes a key intervention in how we think about history, oppression, power, resistance, and sovereignty in Aotearoa); and Camellia Webb-Gannon’s Morning Star Rising: The Politics of Decolonization in West Papua (about West Papuan struggles for independence). These four books illustrated how decolonisation and liberation movements take different forms in different contexts, moving from Aotearoa to West Papua and the United States and encompassing Indigenous sovereignty movements, ongoing struggles against settler-colonialism, and Black liberation and food justice.

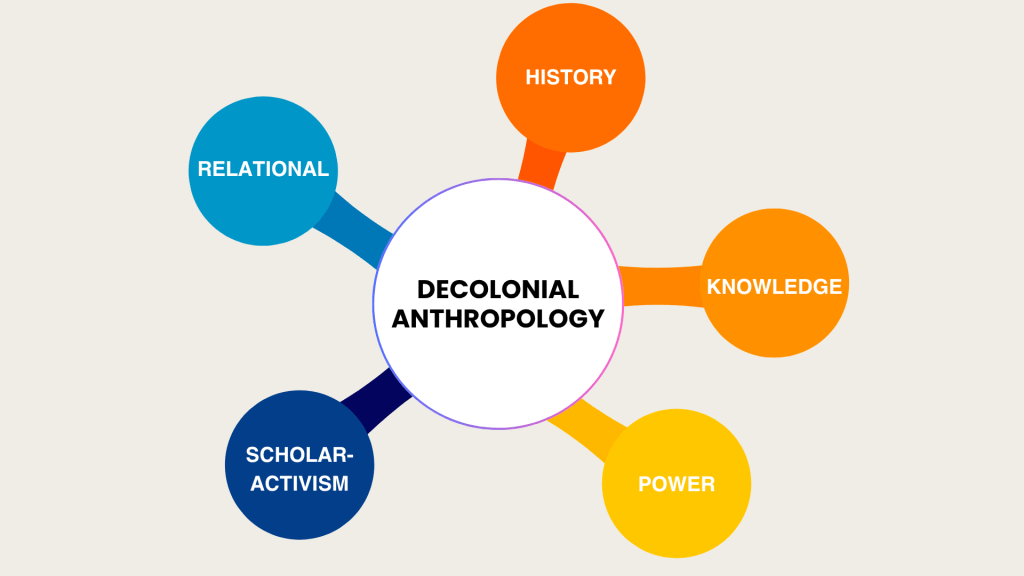

I didn’t realise the consequences of this decision until a student pointed it out to me. We were meeting to discuss potential research project topics and he noted that all three books centered Indigenous sovereignty and liberation movements. He wanted to focus on queer liberation and asked whether I might recommend some books to read about that. His question stopped me short, and I suddenly understood what dropping Black Food Geographies had done for the course. I was teaching as if I still had that book on the reading list and hadn’t adjusted my lectures, which meant that I was introducing students to key course concepts almost exclusively through the lens of Indigenous sovereignty and liberation movements. The decolonial anthropological framework I had developed for the course (Figure 1 below) was designed to apply across diverse liberation struggles (environmental justice, labour movements, abolitionist work, queer liberation, disability justice) but the reading list only included Indigenous case studies.

I shared his observation with the class during our next lecture, explaining what I had done and the unintended outcome. I also said that I had designed this framework to be applied in a variety of contexts and wanted to show how it travelled, and asked the class if they would be interested in spending the last couple of weeks focusing on disability justice. They were, so I assigned the documentary Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution as our reading and wrote a lecture to illustrate how the same analytical questions that helped us understand patterns in Māori sovereignty and West Papuan liberation movements can also reveal patterns in disability justice movements.

I also asked the class for their thoughts about the close reading approach I had been using. Students appreciated the depth of engagement with each book and valued working through them together in class, but many said they were overwhelmed with the amount of reading required and struggled to keep up. They suggested that journal articles, book chapters, or podcasts would be more manageable as they could engage with shorter pieces without the pressure of feeling like they were “failing” if they didn’t finish an entire book. This year’s experience has convinced me to completely redesign the course reading list the next time I teach it.

This experience taught me an important lesson about curriculum design: reading lists make their own arguments about what counts as knowledge, independent of what instructors say in lectures. If you have had a similar experience of course readings communicating something other than what you intended, I would be keen to hear how you navigated this challenge. I’d also love to hear from you if you have taught – or been a student in – a class that experimented with different approaches to course readings.